- Home

- Ron Chernow

The Warburgs

The Warburgs Read online

Acclaim for

RON CHERNOW’S

THE WARBURGS

“Ron Chernow’s blockbuster history traces the heart-rending saga of this German-Jewish banking family.… Despite his scrupulous documentation of sources, Chernow is never less than readable. A graceful and lucid writer, he offers old-fashioned narrative in the grand style.”

—New York Newsday

“The history of a fascinating family.… What we learn about in this book is people.… Chernow is very good at bringing them to life. He has a sharp eye for detail.… One can open the book anywhere and enjoy it.”

—New Republic

“Ron Chernow … has made the stories of these four brothers the cornerstones of a dark, though not quite tragic, family saga. [He is] a graceful writer with an eye for the telling anecdote.… The result is a book of considerable pathos and immediacy—Through his portrait of this complex dynastic organism, he sheds interesing light on various larger historical themes.”

—Boston Sunday Globe

“Excellent family history.… This chronicle of one of the most important banking families in history tells us much about the people.… A great, and lengthy, saga.”

—The Times (London)

“The Warburgs stand revealed as a family more fortune-kissed, fated and fascinating even than the Kennedys, and … just as important … and now their story has been ably told.”

—New York Daily News

RON CHERNOW

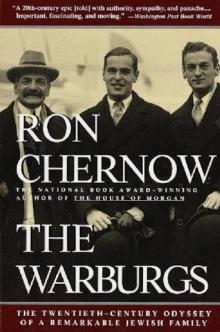

THE WARBURGS

Ron Chernow holds degrees in English literature from Yale and Cambridge. His articles on business, politics, and history have appeared in more than thirty national and regional publications. His celebrated first book, The House of Morgan, won the National Book Award for nonfiction. The Warburgs was awarded the Columbia Business School’s 1993 George S. Eccles Prize for Excellence in Economic Writing, and was named a Notable Book by both The New York Times and the American Library Association. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Valerie, a sociologist.

Books by RON CHERNOW

The House of Morgan

The Warburgs

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, AUGUST 1994

Copyright © 1993 by Ron Chernow

Family tree illustration copyright © 1993 by Anita Karl and Jim Kemp

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1993.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Random House edition as follows:

Chernow, Ron.

The Warburgs/Ron Chernow.

p. cm.

I. Warburg family. 2. Jewish bankers—Biography. 3. Jews—

Germany—Biography. 4. Jews—United States—Biography. I. Title.

DS115.C42 1993 943′.004924′00922—dc20

[B] 93-16599

eISBN: 978-0-307-81350-3

Author photograph © Marion Ettlinger

v3.1

To

VALERIE

and

MELANIE

“But the essential point which most non-Jews overlook and which forms the very crux of the Jewish tragedy, is that those Jews who are giving their energies and brains to the Germans are doing it in their capacities as Germans and are enriching Germany and not Jewry, which they are abandoning.… They must hide their Judaism in order to be allowed to place their brains and abilities at the disposal of the Germans. They are to no little extent responsible for German greatness. The tragedy of it all is that whereas we do not recognize them as Jews Madame Wagner does not recognize them as Germans, and so we stand there as the most exploited and misunderstood of people.”

— CHAIM WEIZMANN to Lord Balfour,

December 12, 1914

“A non-German cannot possibly imagine the heartbreaking position of the German Jew. German Jew—you must place full emphasis on both words. You must understand them as the final product of a lengthy evolutionary process. His twofold love and his struggle on two fronts drive him close to the brink of despair.”

—JAKOB WASSERMANN,

My Life as German

and Jew

“When refugees meet and exchange stories about their escape from Hitler and their lives abroad, each has a unique story to tell, yet each story is like all the others: a life bravely made over but also a dream lost forever.”

—PETER GAY,

The Jews of Germany:

A Historical Portrait

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prelude

PART ONE

THE EMERGENCE OF THE WARBURGS

1. The Matriarch

2. The Imperial Theme

PART TWO

THE RISE OF THE MITTELWEG WARBURGS

3. Meschugge Max

4. Tragicomic Brothers

5. The Sage and the Serpents

6. Magic Mountain

7. A Small Duchy in Westchester

8. The King of Steerage

9. Secret Furies

10. Shy Warrior

11. The Endangered German

12. Uptown, Downtown

13. Iron Cross

14. The Collapse

PART THREE

THE FALL OF THE MITTELWEG WARBURGS

15. Phantom Castle, Phantom Peace

16. The Murder Exploding Detachment

17. The Royal Couple

18. A Season in Hell

19. The Chemistry of Hate

20. Warburg Redux

21. Capitalist Collectives

22. A Stranger in Paradise

23. Account X

24. Blue Boys

25. The Country Cousin

26. Journey into Fear

27. New Deal Noodles

28. Beat the Devil

29. Unseen Menace

30. The Closing Doors

31. Partition

32. The Twilight Dynasty

33. Orphans of the Storm

PART FOUR

THE WARTIME INTERREGNUM

34. Surreal Saviors

35. Deathwatch

36. Little Man and Fat Boy

37. Charnel House

PART FIVE

THE RETURN OF THE ALSTERUFER AND MITTELWEG WARBURGS

38. The Upstart

39. Our Aryan

40. Itinerant Preacher

41. Museum Pieces

42. The Cousins Club

43. My Viking

44. Enemy of the City

45. The Quality of Mercy

46. The European

47. Fathers and Sons

48. Forgotten Gravestone

49. A Town of Strangers

Appendix

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Notes

PRELUDE

The German Jews were a people shipwrecked by history. Arguably the most productive group of Jews in history, they were also, in many ways, the least typical. Few groups have been so admired for their achievements or so maligned for their attitudes. Persecuted by other Germans as too Jewish, they were often scorned by other Jews as too German. Their existence rested on a tenuous illusion of acceptance until the Nazis came along and tore that dream to tatters. People still puzzle over why these bright, industrious people were so blind to a mortal threat to their existence. In frustration, some Jews deny them the dignity of their tragedy.

This book attempts to clarify the mystery through the epic story of one of the world’s mo

st distinguished Jewish families: the Warburgs. No less than the Rothschilds, they were revered as Jewish royalty. A huge, charming, and gregarious clan with enormous joie de vivre, they may rank as the oldest, continuously active banking family in the world, tracing their ancestry to the sixteenth century. This ancient lineage permits a comprehensive look at Jewish evolution on German soil.

It is always dangerous to generalize about a clan as diverse and individualistic as the contradictory, opinionated Warburgs. But as a rule, one can say that they exhibited all the enterprise, daring, and philanthropy of the Jewish community in Germany. With their unfailing energy and high spirits, they adored music and literature, light verse and amateur theatricals, elegant parties and outrageous pranks. They financed German industry, influenced its politics, and enriched its culture. In fact, they excelled in so many areas—producing not only notable bankers, but eminent scholars, politicians, scientists, artists, musicians, philanthropists, socialites, and art patrons—as to rival such protean families as the Huxleys and Jameses. Their story exhibits the abundance of German-Jewish achievement and the eerily close fit of German and Jewish culture.

The Warburgs also displayed the shortcomings of German Jews. They could be snobbish, arrogant, and status-conscious, especially toward their Eastern European brethren. They were often rigid, authoritarian parents. Superpatriotic and steeped in German culture, they exhibited a fierce, sometimes uncritical, devotion to Germany until it was too late. Seemingly heedless of the darker side of the German psyche (although some family members were all too aware of it) and subservient to the state, they were generally ill equipped to deal with the tragedy that befell them. The Warburgs didn’t love Germany wisely but too well.

Through the prism of their history, one sees all the forces that shaped the German Jews: their emancipation in Imperial Germany; their striking emergence in Weimar Germany; their persecution and expulsion in the Third Reich; and their stamina in America, England, Israel, and elsewhere. Few Jewish families so robustly exploited the opportunities open to them under the kaiser or suffered so grievously because of them. Because the Warburgs intermarried with the Schiffs and Loebs of New York, their story also traces the development of the German Jews abroad. Since part of the family returned to Germany after the war, their chronicle carries the story right up to the present.

The Warburgs owed much of their early success to Rothschild patronage and they later occupied an analogous place in Jewish charities. As the Rothschild star was dimming in the early twentieth century, the Warburg star shone most brightly. The contrast between the families is instructive. The power of the Rothschilds arose from the mysterious interplay between private banks and royal courts. The Warburgs, by contrast, were modern, proudly democratic, and closely allied with the new industrial classes. Viewing themselves as free, independent citizens of Hamburg, they identified with its ethos of social mobility, unfettered trade, and democratic politics.

Unlike other Jewish banking dynasties, the Warburgs never blended into the aristocracy and refused to be baptized or ennobled. They straddled two worlds, hovering between the Jewish community and gentile high society, accepted by both but never quite certain where they belonged. They tested the limits of tolerance in hitherto forbidden realms in politics, scholarship, and industry—all without surrendering their Jewish identity. As a result, they highlight in vivid form the baffling dilemmas faced by German Jews who wanted to retain their original identity and yet succeed in the larger society.

Whatever their hidden torment, the Warburgs negotiated their way through society with élan and a magnetic confidence. They escaped the physical and psychological ghettos that had penned in Jews. This was a new sort of Jewish family: glamorous, cosmopolitan, versatile, seductive, and almost perilously self-confident. Their story is more than just the tale of German Jews, for it dramatizes the emergence of the Jewish people in the modern world. It also provides a panoramic view of Germany over the past century, the rise of the American Jewish community, and the creation of the state of Israel.

It is a tragic story of doubt beneath a veneer of self-assurance. Like other German Jews, the Warburgs struggled with an insoluble identity crisis, trying to solve the riddle of who they were. Their fragmented identity affected their business decisions, marriage choices, and political activities. They hoped these tensions would ebb with emancipation. Instead new freedoms only spawned new problems, including the powerful temptation of intermarriage and Christian envy. The Nazis would exploit the identity conflict among German Jews, which weakened their capacity to withstand assault.

If identity confusion was the source of psychological pain, it was also the crucible of creativity. They were assimilated enough to enter the upper echelons of society in Hamburg, New York, and London, but the Warburgs were never wholly accepted. This enabled them to combine an outsider’s perspective with an insider’s entrée. Often seeing things from a somewhat skewed angle, they tended to peer deeper into their times than their contemporaries.

As with other German Jews, the Warburgs displayed ambivalence about their religion. Long arrayed among the wealthy, paternalistic elders who governed the Jewish community, they had shed most of their spirituality by the time Hitler seized power. They were suspended between a religious past they had lost and a secular future they hadn’t found. Rational in outlook, they sometimes felt embarrassed about a religion that seemed encrusted with musty superstition. They kept a wary, uneasy distance from things “too” Jewish, even though the values of Judaism permeated their lives, history, and culture.

Glandular optimists, the Warburgs tried to reconcile the contradictions of being Jewish and German, nationalist and internationalist, traditional and modern. They struggled to forge new syntheses in order to transcend these divisions. They wanted to square the circle, to make the world whole. But the world didn’t allow them the luxury of this tolerant cosmopolitanism. In the end, they were forced to choose among clashing aspects of themselves. As with many German Jews, they discovered that it didn’t matter how they defined themselves. In the end, Adolf Hitler would do it for them.

Brooklyn Heights

January 1993

Part One

THE EMERGENCE OF THE WARBURGS

——

Sara Warburg.

(Warburg family, Hamburg)

CHAPTER 1

––

The Matriarch

Jews settled as far north as the Rhineland after the Romans destroyed the Temple in A.D. 70. Far from feeling alien, these winegrowers and craftsmen felt rooted in Germanic soil. But their pastoral idyll was shattered by the religious zealotry of the eleventh century. Butchered by the Crusaders, they were expelled from their farms and forced into moneylending. During the Black Death, roving flagellants cursed the Jews for supposedly causing the bubonic plague by poisoning wells. They were also periodically accused of draining blood from Christian children to bake unleavened Passover bread—the so-called blood libel. Like dark, disturbing figures from a grim fairy tale, the Jews would secretly linger on in the German psyche as ghouls tricked out in civilian clothes. This legacy would lie dormant, but never dead, in the culture.

The Warburgs sometimes claim to be Sephardic Jews and fancifully trace their genealogy back to medieval Italy. But the first certifiable ancestor appears in 1559, when Simon von Cassel moved from Hesse to the Westphalian town of Warburg, which was founded by Charlemagne. This picturesque walled town had four stone watchtowers that loomed over a maze of crooked cobbled streets, Romanesque churches, and half-timbered houses. The original Warburg house, built in 1537, still stands.

Imported by the Prince-Bishop of Paderborn, who granted him a Schutzvertrag or protective charter, Simon worked as a money changer and pawnbroker. Stymied by the Church prohibition against lending money at interest, noblemen conveniently recruited Court Jews to sin in their stead and stimulate trade. This created a rare historic case of a minority being segregated in a profitable job ghetto. Still a patchwork of thre

e hundred kingdoms, city-states, principalities, and duchies, “Germany” needed Jewish money changers to exchange currencies among these polities. In the popular mind, Jewish bankers deftly exercised a sinister form of black magic, engendering an explosive mixture of envy and resentment.

Court Jews belonged to a special caste and occupied a paradoxical position. (The Warburgs were, strictly speaking, a minor species of Court Jews called Schutzjuden or “protected Jews.”) However prosperous, they survived at the sovereign’s sufferance and could be repudiated whenever debts grew too burdensome. They hung from a golden thread, suspended between gentiles above and Jews below. What anxious tremors fluttered beneath the comfortable air? For ten years, the Schutzvertrag guaranteed the religious freedom of Simon, his family, and servants. Yet they still paid a higher tax rate than that levied upon Christian residents. While Simon hosted the local synagogue in his home, Jewish corpses had to buried safely beyond the town walls in a special cemetery.

No innate cleverness about money pushed Jews toward finance. Barred from crafts by medieval guilds and from farming by local ordinances, they were shunted into trade or moneylending by default. In Warburg, they couldn’t brew beer, sell shoes or clothing. Like many supposedly “Jewish traits,” moneylending was artificially created by anti-Semitic barriers—even if anti-Semites later loudly decried “financial strangulation” by the Jews.

The Warburgs had settled in a tolerant town that didn’t force them to listen to missionary preachers. They were never penned into ghettos at night or stigmatized by having to wear yellow badges, as in Frankfurt and other sixteenth-century cities. Because they were spared the psychic scars of early persecution, they would move about with extra self-assurance. Yet their background as protected Jews left them with a contradictory legacy. Dependent upon official patronage, Court Jews identified with authority figures who safeguarded their privileged status and they were always warily respectful of the state. More cultured and educated than ordinary Jews, they acted as community elders and felt deeply responsible for poor Jews. Simon’s grandson, Jacob Simon Warburg, headed the Jewish community in the Paderborn bishopric, had the town synagogue in his home, and mediated between Jews and the prince. This ambiguous, hybrid status—neither totally Jewish nor gentile—contributed to the deeply schizoid Warburg character.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton The Warburgs

The Warburgs Titan

Titan Grant

Grant Washington

Washington The House of Morgan

The House of Morgan The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance